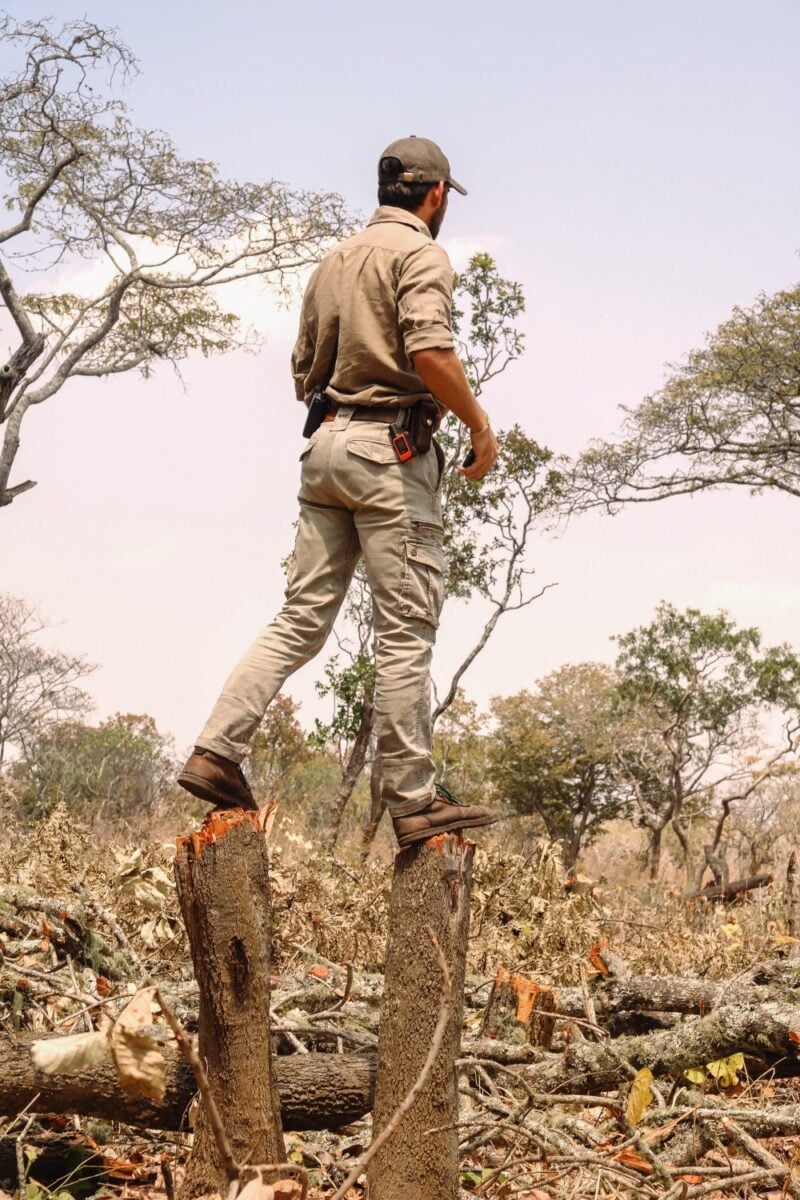

When we reached out to Delport Botma for this story, he was in northern Mozambique’s Niassa province, where he’ll be based for six months, working on a conservation project. Life here is anything but ordinary. Every day work here means flying rangers into remote areas, patrolling for snares, tracking wildlife, and covering terrain that chews through anything less than dependable.

Delport swears by his Jim Green African Ranger Barefoot boots. “They’re great for flying,” he says, “and tough enough for everything that comes after the landing.” His first pair of Rangers has been with him for four years and is still going strong. A year ago, he added the Barefoot version to his kit, and they’ve quickly become his go-to for long days.

Born in Pretoria and raised in Vaalwater, Delport’s passion for the bush began early. He dreamed of becoming a wildlife vet or a helicopter pilot, anything that would keep him close to conservation. In the end, aviation became his way into the work he’d always wanted: a role that combines flying with hands-on conservation.

His “office” changes every day. One morning might mean dropping rangers in areas inaccessible by vehicle, where they’ll spend days on anti-poaching patrol before he circles back to collect them. The next could be an air patrol scanning for snares, poacher camps, or wildlife in distress. When vets need support darting or relocating animals, Delport is often the one flying them in, hauling equipment, and helping on the ground. And when the work is done, you might find him climbing the mountains that frame his bush base, camera in hand.

It’s work that comes with its share of wild stories. One such story he recalls was a black rhino dehorning project. With the introduction of new rhinos into an area, territorial clashes made it necessary to remove horns for the animals’ safety. On the final day of the operation, a late-afternoon storm rolled in just as the last rhino was darted. “There was no place to land, just thick bush, and the light was fading,” Delport says. He dropped a vet off from a hover, two or three metres above the ground, before finding a place to set down himself. Then came the sprint. They raced to the rhino, did the procedure, and had to wake the animal before it got too dark. However, as mentioned earlier, black rhinos can be territorial, and that instinct isn’t solely reserved as a response to other animals. The rhino was very much agitated. “We had to leg it back through the bush to the chopper, with the rhino chasing,” says Delport.

Stories like that underline why Delport’s gear has to hold up both while in the air and in the thick of the bush. His first encounter with the brand was with the Razorback boot, but it was the Rangers that really became part of his kit. Now, he says, it’s hard to imagine working without them. Asked which pair of Jim Green boots he had his eyes on next, “Jim Green has so many boots, it’s like walking into a great restaurant with many options on the menu,” he says. “The Baobab is definitely on my list. But as a work boot, I’m loving the Barefoot. They do exactly what I need.”

In Delport’s world, conservation is about resilience, adapting to whatever the bush throws at you, from storms to charging rhinos. His boots fit the same philosophy: simple, durable, and built to carry you through. Whether he’s in a cockpit above Niassa or running through thick mopane with a rhino on his tail, his Jim Greens have already proved one thing: they’re made for the wild.

Cheers,

The Jim Green Team